- Home

- Greg Steinmetz

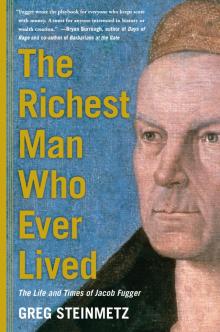

The Richest Man Who Ever Lived: The Life and Times of Jacob Fugger

The Richest Man Who Ever Lived: The Life and Times of Jacob Fugger Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

Introduction

1 SOVEREIGN DEBT

2 PARTNERS

3 THE THREE BROTHERS

4 BANK RUN

5 THE NORTHERN SEAS

6 USURY

7 THE PENNY IN THE COFFER

8 THE ELECTION

9 VICTORY

10 THE WIND OF FREEDOM

11 PEASANTS

12 THE DRUMS GO SILENT

Epilogue

Afterword

Photographs

About the Author

Notes

Bibliography

Index

To my parents, Art and Thea Steinmetz, two Swabians who, like Fugger, know the value of hard work and thrift.

Introduction

On a spring day in 1523, Jacob Fugger, a banker from the German city of Augsburg, summoned a scribe and dictated a collection notice. A customer was behind on a loan payment. After years of leniency, Fugger had finally lost patience.

Fugger wrote collection letters all the time. But the 1523 letter was remarkable because he addressed it not to a struggling fur trader or a cash-strapped spice importer but to Charles V, the most powerful man on earth. Charles had eighty-one titles, including Holy Roman emperor, king of Spain, king of Naples, king of Jerusalem, duke of Burgundy and lord of Asia and Africa. He ruled an empire that was the biggest since the days of ancient Rome, and would not be matched until the days of Napoleon and Hitler. It stretched across Europe and over the Atlantic to Mexico and Peru, thus becoming the first in history where the sun never set. When the pope defied Charles, he sacked Rome. When France fought him, he captured its king. The people regarded Charles as divine and tried to touch him for his supposed power to heal. “He is himself a living law and above all other law,” said an imperial councilor. “His Majesty is as God on earth.”

Fugger was the grandson of a peasant and a man Charles could have easily strapped to the rack for impertinence. So it must have surprised him that Fugger not only addressed him as an equal but furthered the affront by reminding him to whom he owed his success. “It is well known that without me your majesty might not have acquired the imperial crown,” Fugger wrote. “You will order that the money which I have paid out, together with the interest upon it, shall be reckoned up and paid without further delay.”

People become rich by spotting opportunities, pioneering new technologies or besting opponents in negotiations. Fugger (rhymes with cougar) did all that but had an extra quality that lifted him to a higher orbit. As the letter to Charles indicates, he had nerve. In a rare moment of reflection, Fugger said he had no trouble sleeping because he put aside daily affairs as easily as he shed his clothing before going to bed. Fugger stood three inches taller than average and his most famous portrait, the one by Dürer, shows a man with a calm, steady gaze loaded with conviction. His coolness and self-assurance allowed him to stare down sovereigns, endure crushing amounts of debt and bubble confidence and joviality when faced with ruin. Nerve was essential because business was never more dangerous than in the sixteenth century. Cheats got their hands cut off or a hot poker through the cheek. Deadbeats rotted in debtor’s prison. Bakers caught adulterating the bread received a public dunking or got dragged through town to the taunts of mobs. Moneylenders faced the cruelest fate. As priests reminded their parishioners, lenders—what the church called usurers—roasted in purgatory. To prove it, the church dug up graves of suspected usurers and pointed to the worms, maggots and beetles that gorged on the decaying flesh. As everyone knew, the creatures were confederates of Satan. What better proof that the corpses belonged to usurers?

Given the consequences of failure, it’s a wonder Fugger strove to rise as high as he did. He could have retired to the country and, like some of his customers, lived a life of stag hunting, womanizing and feasts where, for entertainment, dwarfs popped out of pies. Some of his heirs did just that. But he wanted to see how far he could go even if it meant risking his freedom and his soul. A gift for rationalization soothed his conscience. He understood that people considered him “unchristian and unbrotherly.” He knew that enemies called him a usurer and a Jew, and said he was damned. But he waved off the attacks with logic. The Lord must have wanted him to make money, otherwise he wouldn’t have given him such a talent for it. “Many in the world are hostile to me,” Fugger wrote. “They say I am rich. I am rich by God’s grace without injury to any man.”

When Fugger said Charles would not have become emperor without him, he wasn’t exaggerating. Not only did Fugger pay the bribes that secured his elevation, but Fugger had also financed Charles’s grandfather and taken his family, the Habsburgs, from the wings of European politics to center stage. Fugger made his mark in other ways, too. He roused commerce from its medieval slumber by persuading the pope to lift the ban on moneylending. He helped save free enterprise from an early grave by financing the army that won the German Peasants’ War, the first great clash between capitalism and communism. He broke the back of the Hanseatic League, Europe’s most powerful commercial organization before Fugger. He engineered a shady financial scheme that unintentionally provoked Luther to write his Ninety-five Theses, the document that triggered the Reformation, the earth-shattering event that cleaved European Christianity in two. He most likely funded Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe. On a more mundane note, he was among the first businessmen north of the Alps to use double-entry bookkeeping and the first anywhere to consolidate the results of multiple operations in a single financial statement—a breakthrough that let him survey his financial empire with a single glance and always know where his finances stood. He was the first to send auditors to check up on branch offices. And his creation of a news service, which gave him an information edge over his rivals and customers, earned him a footnote in the history of journalism. For all these reasons, it is fair to call Fugger the most influential businessman of all time.

Fugger changed history because he lived in an age when, for the first time, money made all the difference in war and, hence, politics. And Fugger had money. He lived in palaces and owned a collection of castles. After buying his way into the nobility, he lorded over enough fiefdoms to get his name on the map. He owned a breathtaking necklace later worn by Queen Elizabeth I. When he died in 1525, his fortune came to just under 2 percent of European economic output. Not even John D. Rockefeller could claim that kind of wealth. Fugger was the first documented millionaire. In the generation preceding him, the Medici had a lot of money but their ledgers only report sums up to five digits, even though they traded in currencies of roughly equal value to Fugger’s. Fugger was the first to show seven digits.

Fugger made his fortune in mining and banking, but he also sold textiles, spices, jewels and holy relics such as bones of martyrs and splinters of the cross. For a time, he held a monopoly on guaiacum, a Brazilian tree bark believed to cure syphilis. He minted papal coins and funded the first regiment of Swiss papal guards. Others tried to play the same game as Fugger, most notably his Augsburg neighbor Ambrose Hochstetter. While Fugger was never richer or more solvent than at the time of his death, Hochstetter, the pioneer of banking for the masses, went bust and died in a prison.

Fugger began his career as a commoner,

the lowest rung in the European caste system. If he failed to bow before a baron or clear the way for a knight on a busy street, he risked getting skewered with a sword. But his mean origins posed no obstacle; all businesspeople were commoners and the Fugger family was rich enough to buy him every advantage. The Fuggers had a knack for textile trading and records show they were among the biggest taxpayers in town. There were nevertheless challenges. Fugger’s father died when he was ten. If not for a strong and resourceful mother, he might have gotten nowhere. Another handicap was his place in the birth order. He was the seventh of seven boys, a spot in the lineup that should have landed him in a monastery rather than in business. He had character flaws like anyone else. He was headstrong, selfish, deceitful and sometimes cruel. He once sent the family of a top lieutenant to the poor house after the aide died and he refused to forgive a loan. But he turned at least one of those flaws—a tendency to trumpet his own achievements—into an asset. His boasts were good advertising; by letting visitors know what he paid for a diamond or how much money he could conjure for a loan, he broadcast his ability to do more for clients than other bankers.

The downside of notoriety was resentment. Enemies pursued Fugger most of his working life and his career unfolded like a video game. They attacked him both head-on and from surprising angles, throwing him progressively more difficult challenges as he rose in wealth and power. Luther wanted to bankrupt him and his family, declaring he wanted to “put a bit in the mouths of the Fuggers.” Ulrich von Hutten, a knight who was the most famous German writer of his time, wanted to kill him. But he survived every assault and accumulated more points in the form of money and power.

Did success make Fugger happy? Probably not, at least not by conventional terms. He had few friends, only business associates. His only child was illegitimate. His nephews, to whom he relinquished his empire, disappointed him. While on his deathbed, with no one at his side other than paid assistants, his wife was with her lover. But he succeeded on his own terms. His objective was neither comfort nor happiness. It was to stack up money until the end. Before he died, he composed his own epitaph. It was an unabashed statement of ego that would have been impossible a generation earlier, before the Renaissance philosophy of individualism swept Germany, when even a self-portrait—a form of art Dürer created during Fugger’s lifetime—would have been regarded as hopelessly egotistical and contrary to social norms.

TO GOD, ALL-POWERFUL AND GOOD! Jacob Fugger, of Augsburg, ornament to his class and to his country, Imperial Councilor under Maximilian I and Charles V, second to none in the acquisition of extraordinary wealth, in liberality, in purity of life, and in the greatness of soul, as he was comparable to none in life, so after death is not to be numbered among the mortal.

Today Fugger is more known for philanthropic works, notably the Fuggerei public housing project in Augsburg, than for being “second to none in the acquisition of extraordinary wealth.” The Fuggerei remains in operation and attracts thousands of foreign visitors a year thanks to investments Fugger made five centuries ago. But Fugger’s legacy is even more enduring. His deeds changed history more than those of most monarchs, revolutionaries, prophets and poets ever did, and his methods blazed the path for five centuries of capitalists. We can easily see in Fugger a modern figure. He was at his core an aggressive businessman trying to make as much money as possible and doing whatever it took to achieve his ends. He chased the biggest opportunities. He won favors from politicians. He used his money to rewrite the rules to his advantage. He surrounded himself with lawyers and accountants. He fed on information. These days, billionaires with the same voracious instincts as Fugger fill the pages of the financial press. But Fugger blazed the trail. He was the first modern businessman in that he was the first to pursue wealth for its own sake and without fear of damnation. To understand our financial system and how we got it, it pays to understand him.

1

SOVEREIGN DEBT

In Renaissance Germany, few cities matched the energy and excitement of Augsburg. Markets overflowed with everything from ostrich eggs to the skulls of saints. Ladies brought falcons to church. Hungarian cowboys drove cattle through the streets. If the emperor came to town, knights jousted in the squares. If a murderer was caught in the morning, a hanging followed in the afternoon for all to see. Augsburg had a high tolerance for sin. Beer flowed in the bathhouses as freely as in the taverns. The city not only allowed prostitution but maintained the brothel.

Jacob Fugger was born here in 1459. Augsburg was a textile town and Fugger’s family had grown rich buying cloth made by local weavers and selling it at fairs in Frankfurt, Cologne and over the Alps, in Venice. Fugger was youngest of seven boys. His father died when he was ten and his mother took over the business. She had enough sons to work the fairs, bribe highway robbers, and inspect cloth in the bleaching fields, so she decided to take him away from the jousts and bathhouses and put him on a different course. She decided he should be a priest.

It’s hard to imagine that Fugger was happy about it. If his mother got her way and he went to the seminary, he would have to shave his head and surrender his cloak for the black robes of the Benedictines. He would have to learn Latin, read Aquinas and say prayers eight times a day, beginning with matins at two in the morning. The monks fended for themselves, so Fugger, as a monk, would have to do the same. He would have to thatch roofs and boil soap. Much of the work was drudgery, but if he wanted to become a parish priest or, better yet, a secretary in Rome, he had to pay his dues and do his chores.

The school was in a tenth-century monastery in the village of Herrieden. Near Nuremburg, Herrieden was a four-day walk from Augsburg or two days for those lucky enough to have a horse. Nothing ever happened in Herrieden and, even if it did, Fugger wouldn’t be seeing it. Benedictines were an austere bunch and seminarians stayed behind the walls. While there, Fugger would have to do something even more difficult than getting a haircut or comb wool. He would have to swear to a life of celibacy, obedience and, in the ultimate irony considering his future, poverty.

There were two types of clerics. There were the conservatives, who blindly followed Rome, and reformers like Erasmus of Rotterdam, the greatest intellectual of the age, who sought to eradicate what had become an epidemic of corruption. We will never know what sort of priest Fugger would become because just before it was time for him to join the monks, Fugger’s mother reconsidered. Fugger was now fourteen and she decided she could use him after all. She asked the church to let Fugger out of his contract, freeing him for an apprenticeship and a life in trade. Years later, when Fugger was already rich, someone asked how long he planned to keep working. Fugger said no amount of money would satisfy him. No matter how much he had, he intended “to make profits as long as he could.”

In doing so, he followed a family tradition of piling up riches. In an age when the elite considered commerce beneath them and most people had no ambitions beyond feeding themselves and surviving the winter, all of Fugger’s ancestors—men and women alike—were strivers. In those days, no one went from nothing to superrich overnight. A person had to come from money—several generations of it. Each generation had to be richer than the one before. But the Fuggers were a remarkably successful and driven bunch. One after the other added to the family fortune.

Jacob’s grandfather, Hans Fugger, was a peasant who lived in the Swabian village of Graben. In 1373, exactly a century before Jacob started in business, Hans abandoned his safe but unchanging life in the village for the big city. The urban population in Europe was growing and the new city dwellers needed clothing. Augsburg weavers filled the demand with fustian, a blend of domestic flax and cotton imported from Egypt. Hans wanted to be one of them. It’s hard to imagine from our perspective, but his decision to leave the village took incredible courage. Most men stayed put and earned their living doing the exact same job as their father and grandfather. Once a miller, always a miller. Once a smith, always a smith. But Hans couldn’t help himself. He was a y

oung man with a Rumpelstiltskin fantasy of spinning gold from a loom. Dressed in a gray doublet, hose and laced boots, he made his way to the city, twenty miles down the Lech River, on foot.

Augsburg is now a pleasant but small city fabled for its puppet theater. A long but doable commute to Munich, it is no more significant in world affairs than, say, Dayton, Ohio. Its factories, staffed by the sort of world-class engineers that keep Germany competitive, make trucks and robots. If not for a university and the attendant bars, coffeehouses and bookstores, Augsburg would risk obscurity as a prosperous but dull backwater. But when Hans arrived it was on its way to becoming the money center of Europe, the London of its day, the place where borrowers looking for big money came to press their case. Founded by the Romans in AD 14 in the time of Augustus, from whom it takes its name, it sits on the ancient road from Venice to Cologne. In AD 98, Tacitus described the Germans as combative, filthy and often drunk, and remarked on their “fierce blue eyes, tawny hair and huge bodies.” But he praised Augsburgers and declared their city “splendidissima.”

A bishop controlled the city when, in the eleventh century, the European economy rose from the Dark Ages and merchants set up stalls near his palace. As their numbers grew, they bristled at the bishop telling them what to do and they chased him to a nearby castle. Augsburg became a free city where the citizens arranged their own affairs and reported to no authority other than the remote and distracted emperor. In 1348, the Black Death hit Europe and killed at least one in three Europeans but miraculously spared Augsburg. This enormous stroke of good fortune allowed Augsburg and other cities of southern Germany to replace ravaged Italy as the focal point of European textile production.

As Hans Fugger approached the city gates and first saw the turrets of the fortification wall, he could be forgiven if he thought Augsburgers did nothing but make fabrics. Bleaching racks covered with cloth spread in every direction. Once inside the gates, he would have been struck by all the priests. The bishop was gone, but Augsburg still had nine churches. Franciscans, Benedictines, Augustinians and Carmelites were everywhere, including the bars and brothels. Hans would also have noticed swarms of beggars. The rich, living in gilded town houses on the high ground of the city’s center, had nine tenths of Augsburg’s wealth and all the political power. They found the beggars unsightly—if not menacing—and passed laws to keep them out. But when the gates opened in the morning and peasants from the countryside streamed in to earn a few pennies sweeping streets or plucking chickens, the guards failed to sort out who was who. The beggars darted by.

The Richest Man Who Ever Lived: The Life and Times of Jacob Fugger

The Richest Man Who Ever Lived: The Life and Times of Jacob Fugger